Designing Wichita

The Chung Report gathers insight from Bill Gardner and others on the state of Wichita as a brand and the key districts that elevate its personality.

20 Dec 2018

This post originally appeared on The Chung Report.

Think about what makes you buy something — whether it’s a house, a piece of clothing or a car. Of course, it has to do its function. If it’s a house, it has to provide enough space for you to live. The car has to get you from A to B.

But there are also hidden elements that you consider whenever you purchase something. What does that car brand say about you? If it’s a Jeep, maybe it says you’re a weekend warrior ready for adventure. If it’s a Honda sedan, maybe it says you’re practical and pragmatic. If it’s a Mercedes, maybe it says you have an eye — and a budget — for the finer things in life.

“There are reasons that you take a brand and you associate with it. And a city is no different than that in a lot of ways. It’s just a much more complex product, but it’s still a product.”

Bill Gardner

“There are reasons that you take a brand and you associate with it,” says Bill Gardner, designer and owner of Gardner Design, a Wichita-based branding and graphic design firm. “And a city is no different than that in a lot of ways. It’s just a much more complex product, but it’s still a product.”

That product has a lot to offer. It has jobs, homes, bars, restaurants, movie theaters, art and music. But those are just the essentials. Every city has them — just like every car goes from A to B. What makes a city unique is its brand and what it says about those who live there.

In this exploration about Wichita’s brand, it’s important to note that everything has a brand, or an essence, whether it’s purposeful or not. Brands can develop organically, just as they can be developed by designers and marketers.

For instance, the Jeep brand wasn’t developed from scratch. It was earned by the vehicle’s reputation. Then, marketers used that reputation to fortify the brand and sell to consumers attracted to it.

That means every district in every city already has a brand defined by what we think about that specific area. Those thoughts could be conjured from the organic aesthetics that pop up because of a certain culture, type of development or era, or they could be conjured from a purposeful aesthetic or visual component that gives us different ideas about the area.

The same is true for an entire city. We think of Nashville a certain way, and Detroit a different way. We think of San Francisco, Austin and New York City in terms of their unique identities.

So what is Wichita’s identity or brand? And how can we use design to either enforce that brand, or create a new one entirely?

A Mercedes car might have a few dozen people involved in the designing process. A city has thousands. They’re business owners, architects, developers, artists and the city employees who develop and implement signage.

So how do you build consistent branding across all of these elements?

On one extreme, you have near-total control of every element. Norway has plans to come close to this by embracing the concept of universal design in all of its public buildings. On the other extreme, you exert zero control and live without any sense of cohesive design standards.

Controlling everything is not only difficult, but also produces sterile and unoriginal spaces. A total lack of governance results in dissonance across the city, creating brand confusion.

“So you almost get to this point where you’ve got to shrink down space,” Gardner says. “If you think back in your life to places you’ve been that really had that cohesion, they were probably districts as opposed to full cities.”

Things like street lamps, directional signage, buildings and murals tell you where you are, and build a connection to a certain place.

“And you can feel it when you drive through that area pretty quick,” Gardner says.

He points out Old Town as an example of this in Wichita. The cobblestone streets, signage and even the old brick buildings immediately clue you into where you are and build a certain feel about it. But Gardner says it isn’t enough to have a cohesive design — it also has to be good.

“If you look at that core signage that’s downtown, it was developed in the early ’90s, and even at the time I hated it,” he says. “Despite the fact that they’ve got functionality, they may not speak relevance to the people that you’re trying to talk to. And that happens in branding. You get to that point where something doesn’t speak to the people that it needs to speak to. Or even worse, it does speak to them, but it speaks of another era, or it speaks of a message that isn’t one that you want to convey.”

Gardner says the signage is like dressing the city in clothes from the ’90s. And there’s a reason we don’t all take our fashion cues from Friends in 2018.

If cohesive, good design is so important to creating memorable city districts which feel good to be in, whose job is it to create them?

Like most cities, Wichita does have a design council that makes recommendations on public projects, but the city doesn’t really have anyone advocating for district design. That’s mostly up to developers, business owners and architects, who shape design on a project-by-project basis or advocate through organizations like the Old Town Associationor the Douglas Design District.

“There seems to be a lot of pride in place lately,” says Allyson Wray Kuhn, interior architectural designer for GLMV Architecture, a firm that has designed several high-profile structures in Wichita, including INTRUST Bank Arena, Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport and the Advanced Learning Library. “People really wanting their space to be a reflection of them and their lifestyle and what they like to do. You see these little districts popping up that really are reflective of a diverse community.”

Kuhn and GLMV project manager Chris Kliewer point out that Wichita has more defined districts with unique designs than most realize, but the design is much more subtle.

“I just think there’s a variety of design pockets in Wichita,” Kuhn says. “You go to Old Town, and you get the red brick warehouse scene. You go over to Delano, and it’s the … small town feel that you talk about Wichita having. You see that a lot in Delano with the smaller spaces and the lower roof lines.”

In other cities, these districts are more clearly defined. You know when you’re in Kansas City’s Power & Light District, Westport or Country Club Plaza. In Oklahoma City, you know when you’re in Bricktown, and in Tulsa, you know when you’re in Utica Square.

So how do other cities create vibrant, distinguishable districts without limiting the creative freedom of their architects, designers and developers? And why is it so important for Wichita to keep up?

People are more aware than ever of the branding with which they connect. Social media has made art and culture more accessible, while ushering in the concept of personal branding. Today, people are connoisseurs and curators of their own brands, which are reinforced by the places they go, clothes they wear and the products they buy.

And for many, their personal brand includes the city and district in which they choose to live, requiring cities to think more like companies to ensure their brand sells.

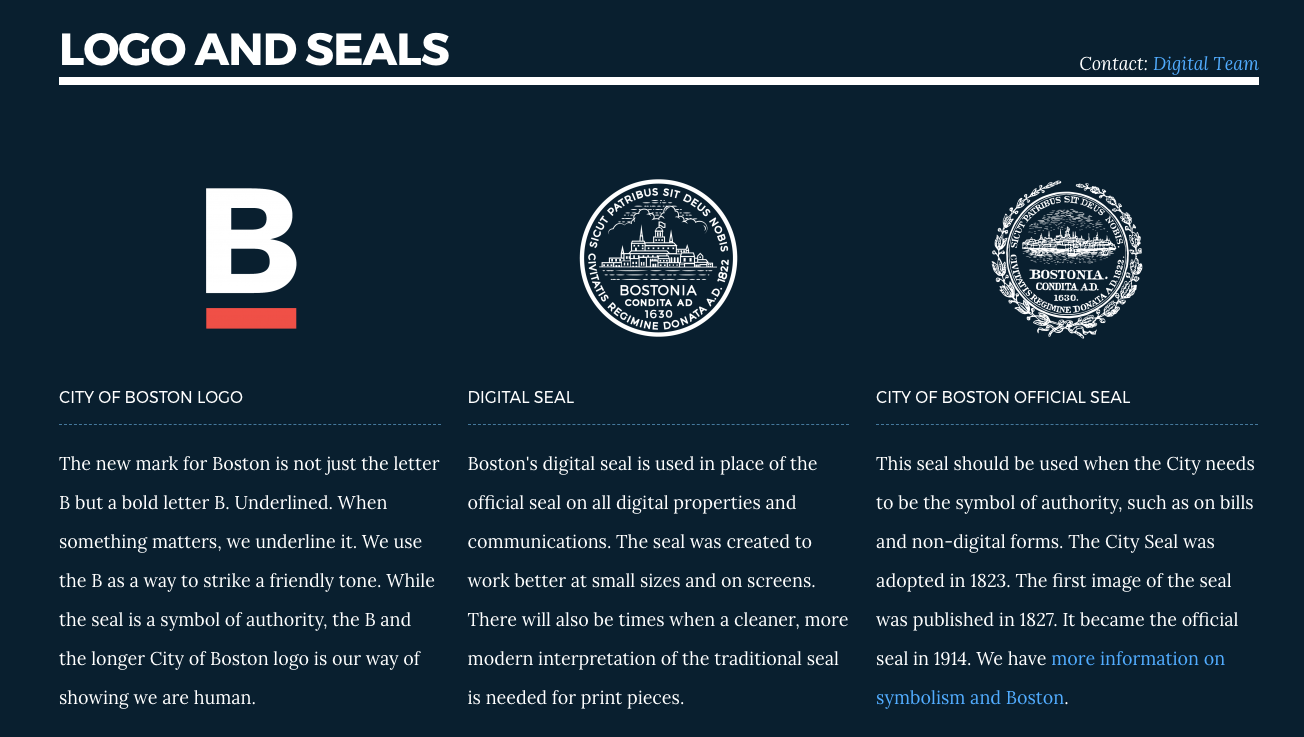

Boston is a city that understands this well, with an accessible web page full of brand standards, including smart, modern designs and even adjectives the city can use to describe itself and its residents. All of the city logos are also there and ready to download with descriptions on how and where they should be used.

To contrast, Wichita’s city standards for the East Douglas Historic District are vague, dense and incredibly outdated. Nomar’s are better, but still not nearly brand-focused enough. Instead, they focus on function of signage and architecture features.

In addition to updating these district-defined brand standards, the city needs to tell outsiders what it means to live in Wichita — not in 1994, but today. That means modern design aesthetics that appeal to a wide range of people living today.

Creating a road map similar to Boston’s would go a long way to set our intentions as a city — both in voice and in look. When those intentions are made, others can follow suit, creating city-wide appeal for a wide range of people.

Ultimately, we have to start thinking of our city as something we need to sell, and that means we have to have an appealing brand.

On the surface, it looks like Wichita’s private businesses and organizations are getting more design-centric. New developments are designed with a contemporary aesthetic that looks sleek and modern. When Reverie moved locations, it opened up with a much more polished, sophisticated look. So did Cargill with its new headquarters. Plans for Naftzger Park and the surrounding development also look updated and well designed.

And it makes sense. More developers, district leaders and consumers are beginning to take note of the design that speaks to them, and the people they want to attract.

Wichita State University, which essentially behaves like its own district, came to Gardner Design to have Gardner’s team rebrand the University with a new logo and signage.

The results are on campus today, with standardized waypoint signage that refers back to the logo through consistent colors and shapes. They’re simple, but effective.

“Wichita State had two logos that both said WSU, with a piece of wheat over it,” Gardner says. “One was the athletic. One was the academic. One was very light and ephemeral. The other was very masculine, and sports-oriented. And it was trying to bring those two together in such a fashion that it could kind of serve both gods, which is a challenge within a campus identity. But we also established a font.”

Between the new logos, font and signage, Gardner’s team was able to create a succinct district feel without relying on the brick architecture that had been used for decades in the past. Now that WSU is building new buildings outside of that long-held design standard, other elements are there to hold it all together graphically.

Gardner says this type of thinking is also leaking out to other parts of the city. In South Wichita, entrepreneur Jeff Lange is investing to create several horse-themed districts, including IronHorse Manufacturing Park and the larger CrossGate District.

“As we started driving, looking around, reading history and going through that area, one of the things we noticed was there’s a lot of folks that graze their horses down here,” Gardner says. “We’re going, ‘Okay, what’s a sign that you are in an equestrian area, physically?’ Well, if I were driving in the Bluegrass areas of Kentucky I would see these three-railed white fences rolling alongside the roads. Or I would see cross gate fencing.”

Once the name was decided on, Gardner’s team went to work creating horse-related elements that elevate the area’s aesthetic and relate back to its history to give the district a specific and unique sense of place.

“It’s critical for a design to be able to respond to its local environment in whatever way that is,” Kliewer says. “That may have a stronger impact on you as a designer than what people that have lived there for 50 years are thinking.”

It’s not that everyone in Wichita realized the south side was horse-centric. It’s that a designer did some digging to learn more about a district, and brought that hidden history to the forefront.

Kuhn says these types of design decisions in one area can have an impact on the overall aesthetic standards of the city.

“You have somebody come into one area, and the person next to you notices, and they do something really cool to try to meet that — or kind of raise their standards,” she says. “It’s just the domino effect.”

If the city of Wichita could create an updated and accessible design standard for the city and showcase these new, higher standards in a few districts, it could truly change the way our entire city thinks about, and implements, design — without ever forcing specific standards on any private development.

And if we can change the way we use design, we can set an intention for everything we see, touch, feel and experience in this city. We could think differently about the first impressions a restaurant gives a new customer, the buildings we see along the river, the street signs that tell us how to get to that downtown museum, the sidewalks, statues, park benches and storefronts. We could think differently about the entire experience of Wichita.

Design is already all around us. It’s time to start thinking about it.

The Chung Report is an online initiative for every person who believes Wichita is worth saving. Its core purpose is to stimulate collaboration, business growth and entrepreneurial energy.

Need a creative partner

for your next big idea?